Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted. – Matthew 5: 4

What are we to make of, “Thomas, one of the twelve, called Didymus”? When Jesus said that He intended to go into Judaea again, His disciples advised Him not to go there. “Master, the Jews of late sought to stone thee; and goest thou thither again?” When Jesus makes it clear that He will go back to Judaea, Thomas says to his fellow disciples, “Let us also go, that we may die with him.” Is there any greater loyalty than that? Thomas knows Christ cannot hope to survive if He goes to Judaea, but nevertheless he decides to stand by Christ to the end. Yet that same Thomas, also called Didymus, declares, after the risen Lord appeared to the other disciples when Thomas was not present, “Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails, and put my fingers into the print of nails, and thrust my hand into his side, I will not believe.” We know how that story ends:

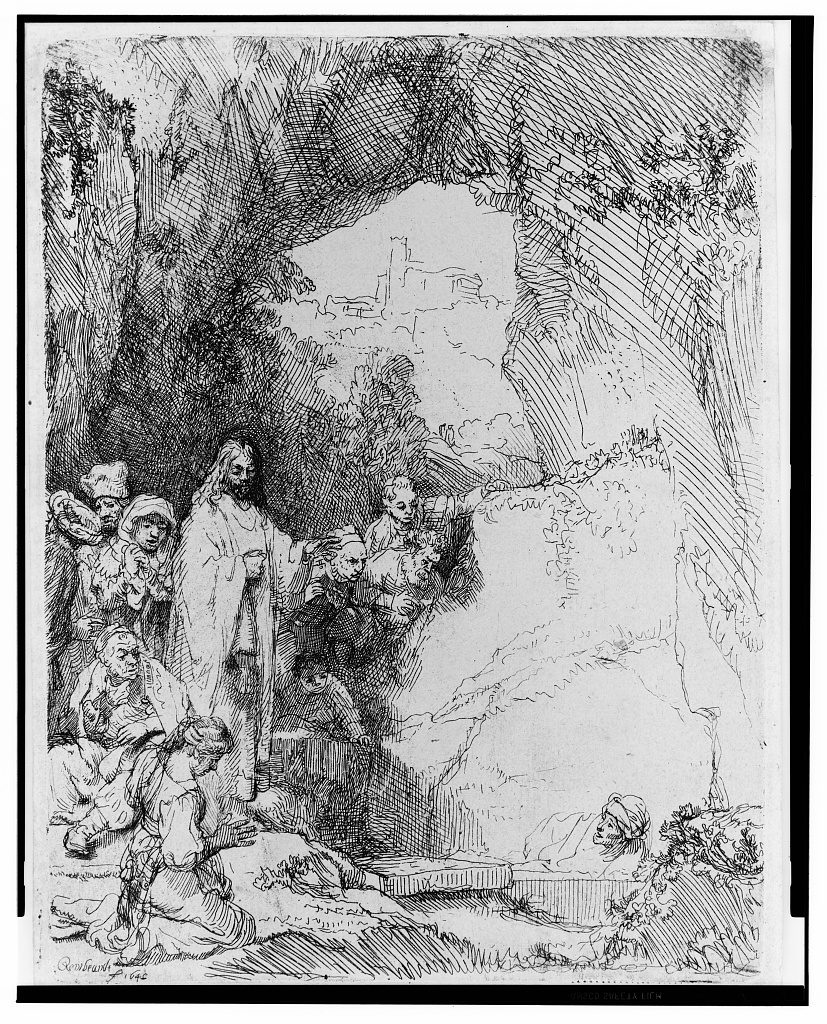

And after eight days again his disciples were within, and Thomas with them: then came Jesus, the doors being shut, and stood in the midst, and said, Peace be unto you. Then saith he to Thomas, Reach hither thy finger, and behold my hands; and reach hither thy hand, and thrust it into my side: and be not faithless, but believing. And Thomas answered and said unto him, My Lord and my God. Jesus saith unto him, Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed. John 20: 26-29

Through all the Christian centuries the label “doubting Thomas” has been applied to those who lack faith. Is the label unfair? Well, Thomas does doubt His Lord. But would any of the other apostles have fully believed in Christ’s resurrection from the dead if they had not been present when He appeared to them in the flesh? There was one, and that one was John: “Then went in also that other disciple, which came first to the sepulchre, and he saw and believed.” Why John? Why did he see the empty tomb and believe? John saw and believed because he conquered his rationalism on the night of the last supper when he laid his head on Christ’s sacred heart. Thomas was not a moral pariah like Judas Iscariot, he loved much; he was willing to die for Christ. But he couldn’t completely believe till he saw the risen Lord. When he did see him in the flesh, he declared, “My Lord, and my God.” He wanted to believe, but he needed help to overcome his rationalism, and our Lord had compassion on him and gave him the help he needed. And then He speaks to us and tells us that we shall be blessed if we believe without having seen what Thomas saw, the risen Lord.

I’m at the age where death is no longer a mere abstraction to me. I’ve seen it close up in the seemingly lifeless faces of loved ones. “Is this the promised end?” My rationalism tells me, ‘yes’ – that horrid monster death is the promised end for all things mortal. I, like Thomas, when the rational mind predominates over my heart, doubt the reality of the risen Lord. I am not John. But I do have that within which is part John; my heart says, “Lord, I believe, help my unbelief.”

In Milton’s Samson Agonistes, Samson, after he has been blinded by the Philistines, is visited by Delilah who offers him her body, telling him that there are still pleasures that a blind man can experience. Samson rejects the offer with a most striking vehemence. And he does so because he knows that the temptation of Delilah is the temptation he is the most susceptible to. All of us, the people of the 20th and 21st centuries, are born into the culture of rationalism. It is in our mother’s milk and the bottled milk we feed upon; it has been woven, under the guise of theology, into our churches, and it has been woven into our culture under the guise of science. We must react with violence, the type of violence that taketh the Kingdom of Heaven by storm, against the culture of rationalism that presses down upon us in church and state.

The Holy Ghost resides in the human heart. He is the comforter that we need if we are to be like John: “He saw and believed.” This is why we cannot, as the modern day conservatives suggest we do, combat the liberals’ rationalism with what we believe to be the correct rationalism. There is no correct rationalism. Christ’s resurrection from the dead is not rational. And we must believe that Christ rose from the dead. If we don’t believe in that stunning, startling, unscientific conquest of dumb nature, there is no use continuing any further with the charade of life. I once saw a modern movie in which the hero tells his pregnant girlfriend to get an abortion, because, “This is a trashcan world.” That cuts through all the liberal rhetoric about the brave new world of love, equality, and freedom – “This is a trashcan world.” If Christ be not risen, we are maggots crawling on a trash heap. The love that once was there in Christian Europe, the Christian Europe that the liberals denounce and the church men tell us never existed, allows us to see the risen Lord. We see Christ without actually touching His side and His hands, because the people who believed without seeing Christ in the flesh did see Him in the love that once was there at their racial and familial hearth fires. Our fight for the European hearth fire is the fight for our Jesus, who tells us that even death, that horror of horrors, will not separate us from those we loved here on earth — in Him and through Him, by the power of the Holy Ghost, who dwells in hearts of flesh.

Robert Frost is often quoted by conservatives because he makes reference to God, but Frost did not take the road less traveled, he took the well-traveled road of a vague, impersonal God, who did not transcend the natural world. That well-traveled road, the road of Greek rationalism, leads us to a world of faithlessness. Christ chose Thomas as one of the twelve, because he had that within, “Let us go and die with him,” which transcended rationalism. He couldn’t quite believe, but he was willing to fight for a man who seemed more than man. He was like unto the followers of Odin: “It might be hopeless, but we will fight to the last man for our Lord and kinsman.” It is that feeling of pietas our Lord builds on. He can enter human hearts, hearts that love, and turn rational minds inward to the Lord of human hearts. When that miracle occurs, the doubting Thomas says, “My Lord and my God.”

Let us never forget that Greek rationalism led the great poet Homer to despair. His vision of the afterlife in The Odyssey is a vision of nothingness. And Sophocles, in Oedipus Rex, tells us that it is better to never have been born. Is that the ‘vision’ we want to build upon? Do I want that vision in my heart when I look at the seemingly lifeless faces of my loved ones who have died in this world? Is that the vision I want in my heart as I face my own death? Please God, send us the Comforter and give us the heart to conquer the rationalism within our own souls and the ever-encircling gloom of rationalism in the hostile liberal world around us.

In the “Grand Inquisitor” chapter of The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoyevsky accurately depicts the false path, the path of rationalism, which the organized Christian churches took into Satan’s dark woods. The human heart seems to be a labyrinth in which a man can get lost. But that labyrinth is the only path to Christ, because the Holy Ghost dwells there. The easy road to God on the rationalist Celestial Railroad is a road that leads to hell. If we constantly stare at dumb nature, we will not see God, we will see a spiritual void which we will try to fill with nature’s gods and nature’s opiates. We must hold out for “all or nothing.” Unamuno went back and forth from faith to doubt because he could never quite conquer his rationalism. We who are about to die cannot be rationalists. For the sake of our souls, for the sake of our loved ones, we must take the path less trodden on, the path of faith in a personal Savior who transcends reason.

In the late 1960s, the liberals made explicit what had been implicit in the European world since World War I ended – Rationalism, with its attendant worship of science and the noble savage was the new religion of the modern Europeans. One of the ugliest manifestations of that new religion was the development of death and dying courses in the universities. In those courses, the liberals taught young men and women that death was not something to be afraid of. Why did we no longer need to fear death? Was it because the old, old story of Jesus and His love was true? Of course not. The liberals told us that we did not have to fear death because human beings were mere creatures of nature. We were not sons and daughters of Christ who were not meant to die – we were just natural entities destined to return to the natural world. The atheism of the gypsy in Walter Scott’s novel, Quentin Durward, became the mainstream faith of the ruling liberal elites in church and state:

“To be resolved into the elements,” said the hardened atheist, pressing his fettered arms against his bosom; “my hope, trust, and expectation is that the mysterious frame of humanity shall melt into the general mass of nature, to be recompounded in the other forms with which she daily supplies those which daily disappear, and return under different forms — the watery particles to streams and showers, the earthy parts to enrich their mother earth, the airy portions to wanton in the breeze, and those of fire to supply the blaze of Aldebaran and his brethren. — In this faith have I lived, and I will die in it! — Hence! begone! — disturb me no farther! — I have spoken the last word that mortal ears shall listen to.”

That new-old faith of the liberals is not my faith, nor can it ever be a genuine faith for a human being. How can we have a faith in nothingness? Dylan Thomas was right to rage against the dying of the light. And he was also right to drink himself into alcoholic oblivion when he could not believe in the light. We dare not look on Dylan Thomas from the Mt. Olympus of rationalism – “It’s a pity that he didn’t rest content with nature and nature’s gods as all rational men do.” No! The pity is that Dylan Thomas gave up on his rage against the dying of the light. He stopped raging and succumbed to the rational world of science and the noble savage. There is a light beyond this rational vale of tears. That light has a local habitation and a name. His home is the human heart, and His name is Jesus. +