My heart as great, my reason haply more,

To bandy word for word and frown for frown;

But now I see our lances are but straws,

Our strength as weak, our weakness past compare,

That seeming to be most which we indeed least are.

–The Taming of the Shrew

__________

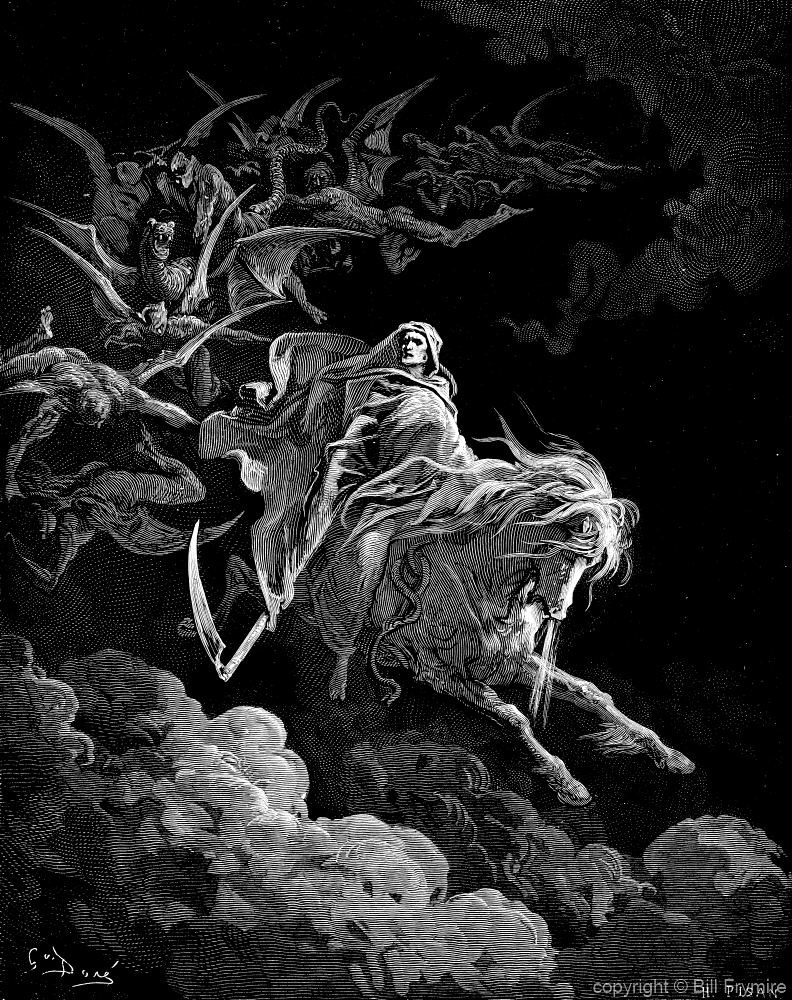

In his sonnets, Shakespeare often expressed frustration at his inability to express himself: “Alack, what poverty my Muse brings forth…” Is that possible? Could such a poet really feel as verbally inadequate as the rest of us? Yes, of course it is possible. In fact, Shakespeare probably felt more verbally impaired than we do. A true poet of the human heart, a man like Shakespeare who saw life “feelingly,” could not help but feel the sharp contrast between a man’s intuitions about the nature of existence and his ability to articulate those heartfelt intuitions. The poetic divers, the men who go down to the depths of the human heart, see that which they can only express in stammering lines. The lesser poets and the theologians, who stay on the surface of life, have no problems of articulation. They spew out banal inanities that defile the human soul, because they violate the mystery of the human heart by turning its complexities into platitudes and syllogisms. It is better to stammer, in the face of the awesome mystery of the human heart, then to defile the mystery by making it conformable to a philosophical premise. The poet who remains faithful to his heartfelt intuitions will bring us to the foot of the cross. The theologians and the theological poets who refuse to go deep will leave us in the first circle of hell, where philosophers endlessly analyze existence without understanding it.

The greatest counter-revolutionary that ever lived, Edmund Burke, felt as Shakespeare did about his heartfelt intuitions concerning the nature of existence. He confessed his despair at what he felt was his failure to adequately convey to his countrymen the satanic nature of Jacobinism:

“I have frequently sunk into a degree of despondency and dejection hardly to be described: yet out of the profoundest depths of this despair, an impulse which I have in vain endeavored to resist has urged me to raise one feeble cry against this unfortunate coalition which is formed at home, in order to make a coalition with France, subversive of the ancient order of the world.”

One feeble cry? Burke did fail, after the death of Robespierre, to convince his countrymen that they had only scotched the Jacobin snake, not killed it. The snake grew in strength and size until it enveloped and consumed, just as Burke had said it would, all of Europe and all of the nations that sprang from Europe. Then was all Burkes’ striving in vain? No, it wasn’t. He may have failed to kill the snake, but he gave his countrymen an extra 150 years before they started to feel the effects of the snake’s grasp. Were it not for Burke, Britain would have turned to Jacobinism in the 18th century instead of in the mid-20th century. It is not a little thing to give one’s countrymen a 150 year period of grace. The effect that Burke’s lonely and unparalleled struggle with the incarnation of Satan within the body politic of Europe had on the British people cannot be over emphasized. He not only turned such poets as Coleridge, Southey, and Wordsworth from rabid Jacobin enthusiasts into rabid anti-Jacobins, he also turned many mad dog Jacobin supporters, who wanted desperately to be whole-hearted supporters of liberty, equality, and fraternity, into tepid, ineffectual moderates, because after Burke only the criminally insane, such as Fox, Price, and Priestly, could still support the Jacobins.

A quick aside on Priestly: He was so unpopular in England because of his radicalism that the English people burned down his house. It’s a pity he escaped the fire, at least that temporal fire, because he fled to America and became a radical sage. His great-granddaughter was Hilaire Belloc’s mother, the same Hilaire Belloc who became the great Catholic defender of the anti-Christian Jacobins. Belloc’s influence was enormous with English Catholics. He was a Catholic Pumblechook who rode his chaise cart over all the lesser carts. He wasn’t able to make English Catholics whole-hearted supporters of Jacobinism, but he lessened their opposition to it, just as Burke had managed to lessen the moderate liberals’ support of Jacobinism. Who knows — had Belloc not supported Jacobinism, it might have come to Britain even later than it did. Such is the power that one man can have for good or evil. Burke, the bred-in-the-bone Christian, wanted to kill Jacobinism in order to save his people. He didn’t kill it, but his passion and his faith kept Jacobinism at bay for many years. Belloc, the intellectual Christian, hastened the end of Christendom through his support for Jacobinism. It will always be thus: a mere intellectual affirmation of faith can never replace a heartfelt love of Christ in and through the people of our racial hearth fire. The former path leads to hell, and the latter path leads to His kingdom come. (1)

What separated Burke from the rest of the conservatives of his century and the 20th century was his rejection of rationalism. He resisted Satan’s great temptation to try to out-reason God. Burke, whose reason was greater than the prideful men of reason, chose like Shakespeare before him to stay with the intuitive wisdom of his people over the wisdom of the philosophers. Truth be told, such reason, separate from revelation and the intuitive life of the people, is incapable of resisting the wickedness and snares of the devil. The modern whites are alone and helpless against the devil and his minions, because they haven’t the humility to place their reason at the service of the bred-in-the-bone wisdom of their ancestors, instead of trying to forge a rationalist path into the future that is unconnected to their European past.

The intellectual Christians first made the satanic break with the blood faith of the European people, but during the course of the 20th century the European peasantry became intellectualized as well, which left the European people without any connection to God or their own people. What is needed is men of reason who reject reason as the penultimate of human existence. Like the hero in Shakespeare’s Cymbeline we must conquer by remaining true to our blood.

“Tis a dream, or else such stuff as madmen

Tongue and brain not; either both or nothing;

Or senseless speaking, or a speaking such

As sense cannot untie. Be what it is,

The action of my life is like it, which

I’ll keep, if but for sympathy.”

The Scriptures tell us that where our treasure lies, so lies our heart. Do we really treasure science and the negro more than the dear, dear land of storybooks? It certainly appears so. To be scientific is to be smart, and that is a highly valued commodity in the land of reason. And the worship of the negro affirms one’s solidarity with the world of science where there is only a natural, noble, savage savior who stands diametrically opposed to the fairy tale Savior of the old world. Burke’s heart, like Shakespeare’s, was with the old world and the Savior of that world. As in all fairy tales you can only get to that old world through charity. You must love your people and God enough to set the wisdom of ‘this world only’ aside as just so much accumulated satanic filth. The narrow gate through our racial home, where the wisdom of the heart lives, is the gate to His Kingdom come.

Shakespeare and Burke have always posed problems for academics and rationalists, be they theologians or philosophers. Both men were and are considered too passionate, too provincial, and too extreme. They can’t be fit into neat little rationalist boxes that the academics, the theologians, and the philosophers love to put men into. But if the intuitions of such poets as Shakespeare and Burke are superior to the ratiocinations of the rationalists, then we need to dive to the poets’ depths if we want to know the truth. But of course modern man does not want to know the truth; he prefers to live in hell.

The most telling evidence of the modern Europeans’ flight from reality is the reception (or should I say non-reception) of the work of Anthony Jacob. Shakespeare always was under-appreciated by the rationalists, and Burke was often hated by the criminally insane men of the left, but neither Shakespeare nor Burke were so completely disregarded as Anthony Jacob has been. This neglect indicates a deep sickness, a sickness unto death, at the heart of our modern European civilization, which, by the way, is no longer a civilization.

The greatest conservative in the 20th century was not Richard Weaver, Russell Kirk, or Thomas Molnar; it was Anthony Jacob. He and he alone wanted to conserve the white race and the white Christian faith rather than an abstract faith and a generic people. Jacob’s reason was as great as any of the conservatives, but unlike the intellectual conservatives Jacob put his reason at the service of his heart. He was one who loved much, like the men and women of antique Europe.

In modern Europe we have men of heart, men who love their people with a deep and abiding love. And we have men of reason, who hate their own people or who are indifferent to their own people. What we need are men like Anthony Jacob; he was a man with a heart of flesh, and he was a man of reason, but he did not make reason his God. He stayed with his heart’s treasure: his people and their God.

Jacob, like the gentle Bard and Edmund Burke, was a poet of the Christian hearth fire: “Charity not only begins at home, it perishes without one.” Is that not the tragedy of modern Europe? Haven’t we lost what Shakespeare called the “quality of mercy” and what Burke called “that charity of honor,” because we have left our hearth fire? At that hearth fire “reigns love and all love’s loving parts…” The Christ of old Europe will still, if we return home, abide with us. +

__________________________

(1) Belloc’s assertion that the French royalty and clergy deserved to die because they were insufficiently Catholic is a prime example of the dangers of an intellectual Christianity devoid of a heartfelt attachment to one’s people. Such a utopian “Christian” faith is just as cruel and un-Christian as the secular utopianism of the Jacobins. It was only the faithful clergymen, the men who refused to take the Jacobin oath, who were executed. And the French nobility, who had the usual canon of sins common to fallen humanity, were not banana-republic tyrants who fed off the blood of their people.

The real tyrants, then and now, are the Jacobins and the intellectual Christians who support them. Those tyrants of reason-gone-mad judge everything by how well it serves their abstract utopias. Thus thousands of aristocrats of the old, non-utopian France could be slaughtered with impunity. And in our modern anti-civilization the death of one black criminal, who is sacred because he is one of “the people,” weighs more in the balance than thousands upon thousands of whites that are slaughtered by the black gods of Liberaldom.